The Barnhart Family of South Bend, Indiana, Family Tree

| Schuyler Colfax | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March iv, 1869 – March 4, 1873 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Henry Wilson |

| 25th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In role December vii, 1863 – March three, 1869 | |

| Preceded by | Galusha A. Grow |

| Succeeded by | Theodore M. Pomeroy |

| Leader of the House Republican Conference | |

| In part December 7, 1863 – March 3, 1869 | |

| Preceded by | Galusha A. Grow |

| Succeeded past | Theodore Grand. Pomeroy |

| Member of the U.Southward. House of Representatives from Indiana's 9th district | |

| In role March four, 1855 – March iii, 1869 | |

| Preceded by | Norman Boil |

| Succeeded by | John P. C. Shanks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Schuyler Colfax Jr. (1823-03-23)March 23, 1823 Manhattan, New York City, U.Due south. |

| Died | Jan 13, 1885(1885-01-13) (aged 61) Mankato, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Republican (afterward 1854) |

| Other political affiliations | Indiana People's Political party (1854) |

| Spouse(s) | Evelyn Clark (thou. 1844; died 1863) Ellen Wade (grand. 1868) |

| Children | Schuyler Colfax 3 |

| Signature | |

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served every bit the 17th vice president of the United states from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the House of Representatives from 1863 to 1869. Originally a Whig, so part of the short-lived People's Party of Indiana, and later a Republican, he was the U.S. representative for Indiana's ninth congressional commune from 1855 to 1869.

Colfax was known for his opposition to slavery while serving in Congress, and was a founder of the Republican Party. During his first term equally speaker he led the try to pass the Thirteenth Amendment to the The states Constitution, which abolished slavery. When it came earlier the Business firm for a final vote in January 1865, he emphasized his support by casting a vote in favor—by convention the speaker votes only to pause a tie. Chosen as Ulysses S. Grant's running mate in the 1868 election, the pair won hands over Autonomous Party nominees Horatio Seymour and Francis Preston Blair Jr. Every bit was typical during the 19th century, Colfax had little interest in the Grant administration. In improver to his duties as president of the U.Due south. Senate, he continued to lecture and write for the printing while in part. Assertive Grant would only serve one term, in 1870 Colfax attempted unsuccessfully to garner support for the 1872 Republican presidential nomination by telling friends and supporters he would not seek a second vice presidential term. When Grant announced that he would run once more, Colfax reversed himself and attempted to win the vice-presidential nomination, but was defeated by Henry Wilson.

An 1872–73 Congressional investigation into the Crédit Mobilier scandal identified Colfax as one of several federal authorities officials who in 1868 accepted payments of cash and discounted stock from the Union Pacific Railroad in exchange for favorable action during the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Though he vociferously defended himself against charges, his reputation suffered. Colfax left the vice presidency at the end of his term in March 1873, and never again ran for office. After he worked as a business organisation executive and became a popular lecturer and speechmaker.[1]

Colfax suffered a heart attack and died at a railroad station in Mankato, Minnesota, on Jan 13, 1885, while en road to a speaking engagement in Iowa.[2] He is one of only 2 persons to have served as both speaker of the House and vice president, the other beingness John Nance Garner.[iii]

Early life [edit]

Ancestral dwelling house of Schuyler Colfax's grandparents William and Hester. Originally built in 1695.

Schuyler Colfax was born in New York City on March 23, 1823, the son of Schuyler Colfax Sr. (1792–1822),[4] a depository financial institution teller, and Hannah Stryker (1805–1872), both of Dutch ancestry, who had married on April 25, 1820.[5] His grandfather, William Colfax, served in George Washington'due south Life Guard during the American Revolution and married Hester Schuyler, the second neat granddaughter of Philip Pieterse Schuyler.[5] [6] : 146–148 and a cousin of General Philip Schuyler.[7] William Colfax became a full general in the New Bailiwick of jersey Militia later on the Revolution and commanded a brigade during the War of 1812.[vi] : 151

Schuyler Colfax Sr. contracted tuberculosis and died on October 30, 1822, five months before Colfax was built-in.[8] His sister Mary died in July 1823, iv months after he was built-in.[5] After the senior Colfax'due south decease, Colfax'south mother and grandmother ran a boarding business firm as their main ways of economical support.[8] Colfax attended school in New York Urban center until he was 10, when family fiscal difficulties caused him to end his formal education and take a job equally a clerk in the store of George W. Matthews.[5] [nine]

Hannah Colfax and George Matthews were married in 1836, and the family moved to New Carlisle, Indiana, where Matthews ran a store which also served as the village post office.[8] [ten] There, Colfax became an avid reader of newspapers and books.[2] The family moved over again in 1841, to nearby South Bend, Indiana, later Matthews became St. Joseph County Auditor.[5] He appointed Colfax as his deputy, a post which Colfax held throughout the viii years Matthews was in role.[5]

Newspaper editor [edit]

In 1842, Colfax became the editor of the pro-Whig South Bend Costless Press, owned by John D. Defrees.[eleven] When Defrees moved to Indianapolis the following yr and purchased the Indiana Journal, he hired Colfax to encompass the Indiana Senate for the Journal.[5] [12] In addition to covering the land senate, Colfax contributed manufactures on Indiana politics to the New York Tribune, leading to a friendship with its editor, Horace Greeley.[13]

In 1845 Colfax purchased the Due south Bend Free Press and changed its proper noun to the St. Joseph Valley Register.[11] He owned the Annals for ix years, at beginning in support of the Whigs, then shifting to the newly established Republican Political party.[14]

Whig Party politician [edit]

While covering the Indiana Senate as a journalist, Colfax too served as the body's assistant enrolling clerk from 1842 to 1844.[fifteen] In 1843, several South Bend residents formed a debating society in which members researched and discussed current events and other topics of interest, and Colfax became a prominent fellow member.[16] The system'south success led it to create a moot state legislature, in which members introduced, debated, and voted on bills in accordance with the rules of the Indiana General Associates.[12] As with the debating gild, Colfax was a prominent fellow member of Due south Bend's moot legislature.[12]

Colfax's success in the debating gild and moot legislature made him prominent enough to take office in politics, and he was selected as a consul to the 1848 Whig National Convention, where he was selected every bit ane of the gathering'south secretaries and supported Zachary Taylor for the presidency.[17] He was side by side elected as a delegate to Indiana's 1849–1850 state constitutional convention.[17] Colfax was the 1851 Whig nominee for Congress in the district which included South Bend, but narrowly lost to his Autonomous opponent.[17] His loss was attributed to his constitutional convention opposition to a mensurate that prevented free African Americans from settling in Indiana.[17]

In 1852, Colfax was a delegate to the Whig National Convention and was selected to serve as a convention secretary.[17] He supported Winfield Scott for president, and afterward Scott was nominated, Colfax took an agile part in the entrada, both through making speeches and authoring and distributing newspaper articles and editorials.[18] In 1852, Colfax's political supporters encouraged him to make a second run for the U.S. House, but he declined.[19]

U.South. Representative (1855–1869) [edit]

In 1854 Colfax ran for Congress again, this time as nominee of the short-lived Indiana People's Party, an anti-slavery movement which formed to oppose the Kansas–Nebraska Deed.[twenty] Colfax won and was reelected six times, and he represented Indiana's 9th congressional district from March 4, 1855, to March three, 1869.[21] During his Firm service, Colfax became a member of the leadership as chairman of the Committee on Mail Office and Mail service Roads, a mail service he held from 1859 to 1863.[22]

Know Nada party affiliation [edit]

In 1855 Colfax considered joining the Know Nothing Party because of the antislavery plank in its platform.[23] He was selected, without his cognition, to be a delegate to the party's June convention, simply had mixed feelings nearly the party and subsequently denied having been a member.[24] Although he agreed with many Know Cypher policies, he disapproved of its secrecy oath and citizenship exam.[25] Past the fourth dimension of his 1856 entrada for re-election, the new Republican Party had get the main anti-slavery party, and Colfax became an early on member.[26]

Opposition to slavery [edit]

Colfax was identified with the Radical Republicans in Congress, and was an energetic opponent of slavery.[27] His June 21, 1856 "Kansas Code" speech[28] attacking laws passed by the proslavery Legislature in Kansas became the nigh widely requested Republican campaign document.[2] Then, as the 1860 presidential election approached, Colfax traveled frequently, delivered many speeches, and helped bind the diverse Republican and antislavery factions together into a unified party that could win the presidency.[two]

Civil War [edit]

Before Lincoln's inauguration, Colfax'southward proper name was put forward by Indiana Republicans for appointment as postmaster general.[fifteen] President Lincoln wrote him a warm letter stating that he considered him qualified and foretelling "a bright future" for the 37-year-sometime, merely that he had already promised a chiffonier position to another Hoosier, Caleb Blood Smith.[29]

At the first of the Civil War Major General John C. Frémont commanded Union Regular army forces in St. Louis, Missouri.[30] On September 3, 1861 Confederate General Sterling Toll defeated Union Brigadier Full general Nathaniel Lyon at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.[31] During the boxing, Price's Confederate troops nether Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky.[32] Frémont was blamed for not reinforcing Lyon, who had been killed in the fighting.[33] On September half dozen, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, nether Frémont's dominance, took Paducah without a fight and established a Union supply base in Kentucky.[32] Colfax, concerned over the Confederate Army's occupation of Kentucky and threatened Union security of Missouri, decided to visit Frémont.[34]

Later on his inflow in St. Louis, Colfax met Frémont on September xiv, 1861, and petitioned him to send troops to cut off Price from capturing Lexington.[35] Colfax believed Frémont had xx,000 troops under his command in St. Louis. Frémont informed Colfax that he merely had eight,000 troops in St. Louis and was unable to spare whatever.[30] In add-on Frémont told Colfax that Lincoln and federal regime in Washington had requested him to dispatch 5,000 of his troops elsewhere.[35] Colfax suggested that Frémont reply that he could not spare whatever troops or Missouri would be lost to the Confederacy. Frémont declined, recognizing that he had a reputation for beingness insubordinate considering he had earlier imposed a controversial Baronial xxx edict that put Missouri under martial police force and emancipated rebel slaves beyond what was included in Lincoln's Confiscation Act, and not wanting to appear unwilling to follow the instructions of his superiors.[xxx] [36] Price captured Lexington on September 20 and threatened to have the whole country of Missouri.[35] Frémont finally responded on September 29, arriving at Sedalia with 38,000 troops and threatening to trap the rebels against the Missouri River.[37] Toll abandoned Lexington, and soon was forced to carelessness the state headed to Arkansas and afterward Mississippi.[37]

On November 1, seven weeks after Colfax'southward visit, Frémont ordered Grant to make demonstrations forth the Mississippi against the Confederates, but non to direct appoint the enemy. The following twenty-four hours Frémont was relieved from control by Lincoln for refusing to revoke his Baronial 30 edict. On November seven, Grant attacked Belmont drawing Confederate troops from Columbus and inflicting Confederate casualties. In February 1862, Grant, in combination with the Marriage navy, captured Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson, forcing Polk to abandon Columbus. The Amalgamated regular army was finally pushed out of Kentucky later on Union General Don Carlos Buell defeated Confederate General Braxton Bragg at the Battle of Perryville in October 1862.

Speaker of the Firm [edit]

Colfax faced a hard reelection campaign in 1862 due to strong antiwar sentiments in Indiana, but won a narrow victory over Democrat David Turpie. Amidst the incumbents defeated that twelvemonth was Speaker of the Firm Galusha Abound. When the 38th Congress convened in Dec 1863, Colfax was elected speaker, despite President Lincoln's preference for someone less tied to the Radical Republicans.[2] Birthday, Colfax was elected speaker for three congresses:

- 38th Congress[38]

■ Schuyler Colfax (R–IN) – 101 (55.fifty%)

■ Samuel South. Cox (D–OH) – 42 (23.08%)

■Others – 39 (21.42%) - 39th Congress[39]

■ Schuyler Colfax (R–IN) – 139 (79.43%)

■ James Brooks (D–NY) – 36 (twenty.57%) - 40th Congress[twoscore]

■ Schuyler Colfax (R–IN) – 127 (fourscore.89%)

■ Samuel S. Marshall (D–IL) – 30 (19.xi%)

During his showtime term as speaker, Colfax presided over the establishment of the Freedmen'southward Bureau, and helped secure congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which, when ratified by usa, abolished slavery. Though information technology is unusual for the speaker to vote, except to intermission a tie, Colfax directed the clerk to phone call his proper name after the roll phone call vote had been taken. He and then cast the last vote in favor of the amendment to much applause from its supporters in the House.[41]

Reconstruction [edit]

In 1865, Colfax, along with author Samuel Bowles and Lieutenant Governor of Illinois William Bross, set out across the western territories from Mississippi to the California declension to tape their experiences. They compiled their observations in an 1869 book called Our New West. Included in their volume were details of the views of Los Angeles, with its wide panorama of vast citrus groves and orchards, and conversations with Brigham Young.

On September 17, 1867, Colfax, along with Senator John Sherman, addressed a Republican coming together in Lebanon, Ohio on the political state of affairs in Washington.[42] Colfax said he was firmly against allowing those who participated in the Confederate rebellion to be reinstated in office and control Republican Reconstruction policy. Colfax affirmed that he was not in any style for repudiating the debt caused past the Confederate rebellion.[42] Colfax said Congressional reconstruction would requite security and peace to the nation equally opposed to President Johnson and his southern Autonomous policies. Colfax favored Johnson's impeachment maxim Johnson was recreant, a usurper, and was unfaithful in executing the Reconstruction laws of the land in granting a general immunity to Southerners who had participated in the rebellion. Colfax told Republicans who were tired of Reconstruction to leave the political party and join the Democrats.[42]

Election of 1868 [edit]

Grant Colfax 1868 Campaign Affiche

During the 1868 Republican Convention the Republicans nominated Ulysses Southward. Grant for president.[43] Colfax was selected for vice president on the fifth ballot.[44] Colfax was popular among Republicans for his friendly character, party loyalty, and Radical views on Reconstruction.[44] Amongst Republicans he was known as "Smiler Colfax."[44] Grant won the general election, and Colfax was elected the 17th Vice President of the United States.

On March 3, 1869, the last full day of the 40th Congress, Colfax, who was to be sworn into function equally vice president the adjacent mean solar day, resigned equally speaker. Immediately after, the Firm passed a motility declaring Theodore Pomeroy duly elected speaker in place of Colfax. In function for 1 24-hour interval, his is the shortest tenure of any speaker of the U.Southward. Business firm.[45]

Vice presidency (1869–1873) [edit]

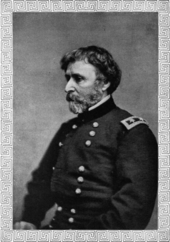

Vice President Schuyler Colfax

Colfax was inaugurated March 4, 1869, and served until March iv, 1873. Grant and Colfax, 46 and 45 respectively at the time of their inauguration, were the youngest presidential and vice presidential team until the inauguration of Bill Clinton and Al Gore in 1993.[46]

Colfax and John Nance Garner, the first vice president under Franklin Roosevelt, are the only ii vice presidents to have been Speaker of the Firm of Representatives prior to becoming vice president, and since the vice president is the President of the Senate, they are the but two people to have served as the presiding officeholder of both Houses of Congress.

Italian unity [edit]

On Friday, January vi, 1871, from Washington, D.C., in a letter published in the New York Times, Colfax recognized and rejoiced in Male monarch Victor Emmanuel Ii's victory of unifying Italy and setting up a new government in Rome. Colfax encouraged Italia to course a Republican authorities that protected religious freedom, regardless of faith, and the civil rights of all individuals, including those who lived in poverty. Colfax said, "for out of this new life of ceremonious and religious freedom volition flow peace and happiness, progress and prosperity, with material and national development, and advocacy every bit surely equally healthy springs flow from fountains of purity."[47]

Ballot of 1872 [edit]

Prior to the 1872 Presidential ballot, Colfax believed that Grant would simply serve ane term as president.[44] In 1870 Colfax announced he would not run for political role in 1872.[44] Colfax's proclamation failed to garner prominent back up among Republicans for a presidential bid, as he had planned, while Grant decided to run for a second term.[44] In addition, Liberal Republican involvement in Colfax every bit a possible presidential candidate alienated him from Grant and the regular Republicans. (The Liberal Republicans believed that the Grant administration was corrupt and were against Grant'south attempted annexation of Santo Domingo.)[44] Colfax reversed course and became a candidate for the Republican vice presidential nomination by informing his supporters that he would accept information technology if information technology was offered.[44] However, Colfax's previously stated intent not to run in 1872 had created the possibility of a contested nomination, and Senator Henry Wilson defeated Colfax by 399.v delegate votes to 321.v.[44] Grant went on to win election to a 2nd term, and Wilson became the 18th vice-president of the The states.[44]

Crédit Mobilier scandal [edit]

In September 1872, during the presidential entrada, Colfax's reputation was marred by a New York Sun commodity which indicated that he was involved in the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Colfax was i of several Representatives and Senators (mostly Republicans), who were offered (and possibly took) bribes of cash and discounted shares in the Marriage Pacific Railroad'south Crédit Mobilier subsidiary in 1868 from Congressman Oakes Ames for votes favorable to the Wedlock Pacific during the edifice of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Henry Wilson was among those accused, but after initially denying a connection, he provided a complicated explanation to a Senate investigating committee, which involved his married woman having purchased shares with her own money, so later canceling the transaction over concerns about its propriety. Wilson's reputation for integrity was somewhat dampened, but not enough to preclude him from becoming vice president.

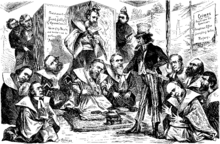

Colfax was castigated for his involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal in this March half dozen, 1873, political cartoon in which Uncle Sam is shown encouraging Colfax to commit hara-kiri.

Colfax as well denied interest to the press, and defended himself in person before a House investigative committee, testifying in January 1873 that he had never received a dividend check from Ames.[5] Despite his protests of innocence, the congressional investigation revealed that in 1868 Colfax had taken a $1,200 gift check for 20 shares of Crédit Mobilier stock from Ames. Colfax had deposited $1,200 in his bank business relationship at the same fourth dimension Ames recorded that he had paid Colfax $1,200.[48] Making matters worse for Colfax, the investigation also revealed that Colfax had received a $4,000 gift also in 1868 from a contractor who supplied envelopes to the federal government while Colfax was chairman of the Committee on Mail Offices and Post Roads, and so had influence in the application of such contracts.[49] Afterward, a resolution to impeach the vice president was introduced in the House, just failed to pass by a by and large party-line vote, mainly because the incidents took place during his tenure every bit congressman (not equally vice president), and because just a few weeks remained in his term.[49]

His political career ruined, Colfax left office under a deject at the end of his term, and never ran for office once more.[43] [49] [50] His only consolation on that bitterly cold[51] March 24-hour interval was a mitt-written letter from Ulysses Grant. In information technology, the president wrote,

I sympathize with you in the recent congressional investigations; that I have watched them closely, and that I am satisfied now as I have ever been of your integrity, patriotism and freedom from the charges imputed as if I knew of my own knowledge your innocence. Our official relations have been so pleasant that I would like to proceed up the personal relations engendered, through life.[52]

Lecturer and business executive [edit]

After leaving function in March 1873, Colfax began to recover his reputation, embarking on a successful career as a traveling lecturer offering speeches on a diverseness of topics. His nearly requested presentation was one on the life of Abraham Lincoln, whom the nation had begun to plow into an icon. With an expanding population that desired to know more details and context about Lincoln's life and career, an oration from someone who had known him personally was an attraction audiences were willing to pay to hear, and Colfax delivered his Lincoln lecture hundreds of times to positive reviews.

In 1875, he became vice president of the Indiana Reaper and Iron Company.[53] On February 12, 1875, having returned to Washington, D.C., to give a lecture, he advised his friends in Congress who were frustrated over the ho-hum footstep of action: "Ah! the style to exit of politics is to become out of politics."[53]

He had remained popular in his home area, and was frequently encouraged to run again for public function, but he always declined. Finally, in April 1882, when pressed to consider becoming a candidate for his onetime U.Due south. Business firm seat in the upcoming election, Colfax appear in a letter to the South Curve Tribune that, while he deeply appreciated how much his friends wanted him to run for public office again, he was satisfied by the 20 years of service he had given during the "stormiest years of our nation's history." He also said that he was enjoying his life as a private citizen, and would neither be a candidate nor accept any nomination for whatsoever office in the future, stating, "only appetite now is to go in and out among my townsmen as a private citizen during what years of life may remain for me to enjoy on this earth."[54]

Personal life [edit]

Ellen M. Wade, second wife of Schuyler Colfax

Colfax was married twice:

- On Oct 10, 1844, he married his babyhood friend Evelyn Clark. She died in 1863; they had no children.

- On Nov xviii, 1868, two weeks after winning the vice presidency, he married Ellen (Ella) Yard. Wade (1836–1911), a niece of Senator Benjamin Wade. They had i son, Schuyler Colfax 3 (1870–1925), who served every bit mayor of South Bend, Indiana, from 1898 to 1901. He assumed office at the age of 28, and remains the youngest person to get mayor in the city's history.[55]

Colfax was a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF). In 1850, Colfax and members William T. Martin of Mississippi and E. G. Steel of Tennessee were appointed to prepare a ritual pertaining to the Rebekah Degree and present a report at the 1851 annual meeting.[56] On September 20, 1851, the IOOF approved the degree and Colfax was credited as its author and founder.[57] [58]

In 1854 Colfax was initiated into the Beta Theta Pi fraternity at DePauw Academy as an honorary fellow member.[59]

Death and burying [edit]

Gravesite of Schuyler Colfax, in South Bend City Cemetery, South Bend, Indiana

On January 13, 1885, Colfax walked from Mankato, Minnesota's Front Street depot to the Omaha depot, about iii-quarters of a mile (1 kilometer) in −30 °F (−34 °C) atmospheric condition, intending to change trains on his way to Rock Rapids, Iowa, to requite a speech.[threescore] 5 minutes after arriving, Colfax died of a heart attack brought on by the extreme common cold and exhaustion.[61]

He was buried at City Cemetery in South Bend.[62] A historical marking in Mankato'southward Washington Park, site of the former depot, marks the spot where he died.[63]

Historical reputation [edit]

Colfax's 20 years of public service concluded in controversy in 1873 due to the revelation that he was involved in the Crédit Mobilier scandal. He never returned to seek political office in part considering he believed that it was best to stay out of politics once leaving part, and in role because he was content with his life every bit a private citizen. Because of his success as a lecturer, his reputation was somewhat restored.

Towns in the U.S. states of California, North Carolina, Illinois, Washington, Wisconsin, Indiana, Iowa, Texas, and Louisiana are named after him. Schuyler, Nebraska, named later Colfax, is the county seat of Colfax County, Nebraska. The ghost town of Colfax, Colorado, was named later on him, as was Colfax County, New United mexican states.

Colfax Avenue in Due south Curve is named in his honour. Colfax's home of his developed years stood on that street, at 601 W. Marketplace St. The metropolis later renamed the street in his honor. The Colfax home was demolished and a Seventh Solar day Adventist church stands on the spot in 2019. There is some other Colfax Avenue in Mishawaka, Indiana, the city only eastward of South Bend. The main east–westward street traversing Aurora, Denver and Lakewood, Colorado, and abutting the Colorado State Capitol is named Colfax Avenue in the politician's award. There also is Colfax Place in the Highland Foursquare neighborhood in Akron, Ohio, in Grant Urban center in New York City's Staten Island; in Minneapolis, Minnesota; in Roselle Park, New Jersey; and a Colfax Street on Chicago's South Side. There is a Colfax Street leading up Mt. Colfax in Springdale, Pennsylvania, in Palatine, Illinois, in Evanston, Illinois, and Jamestown, New York. Dallas, Texas, and ane of its suburbs, Richardson, each have separate residential roads named Colfax Bulldoze. At that place is as well a Colfax Avenue in the San Fernando Valley surface area of Los Angeles and in Agree, California, also as in Benton Harbor, Michigan.

Colfax School was built in South Curve and opened in 1898 just a few blocks from the Schuyler Colfax domicile. The school building still stands in 2019 at 914 Lincoln Manner Westward, although it is no longer a schoolhouse and today is known every bit Colfax Cultural Center. In the '50s and '60s, one of the downtown picture theaters was The Colfax. There is a Colfax Elementary Schoolhouse in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Schuyler-Colfax House in Wayne, New Jersey, which was built by Colfax's ancestors, was added to the National Annals of Historic Places in 1973.[64]

Media portrayals [edit]

Actor Pecker Raymond portrayed Colfax during his time as Speaker in the 2012 Steven Spielberg motion-picture show Lincoln.[65] Raymond was in his early seventies when the film was made[66] while Colfax was in his early forties during the menstruum depicted in the film.[2]

See likewise [edit]

- International Association of Rebekah Assemblies

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- List of vice presidents of the U.s.a. past other offices held

References [edit]

- ^ "Schuyler Colfax, Vice President of the United states of america". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Jan 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Schuyler Colfax, 17th Vice President (1869–1873)". Secretary of the Senate, Washington, D.C. Retrieved April five, 2019.

- ^ Feinman, Ronald 50. (October 31, 2015). "21 Significant Speakers Of The Firm In American History". theprogressiveprofessor.com . Retrieved Apr 7, 2019.

- ^ The Magazine of History

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h BDOA_CS_1906.

- ^ a b William Nelson (1876). Biographical Sketch of William Colfax, Captain of Washington's Body Guard.

- ^ Phelps, Charles A. (1868). Life and Public Services of General Ulysses S. Grant. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard. p. 322 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "Schuyler Colfax (1823–1885)". newnetherlandinstitute.org. Albany, NY: New Netherland Constitute. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Hollister, Ovando James (1886). Life of Schuyler Colfax. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 14–nineteen. OCLC 697981267.

- ^ Brisbin, James S. (1868). The Entrada Lives of Ulysses S. Grant and Schuyler Colfax. Cincinnati, Ohio: C. F. Vent & Visitor. p. 359. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Brisbin, p. 362.

- ^ a b c Brisbin, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Bulla, David Due west.; Borchard, Gregory A. (2010). Journalism in the Civil War Era. New York, NY: Peter Lang. p. four. ISBN978-1-4331-0722-i – via Google Books.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans (1991). Historical Dictionary of Reconstruction. New York: Greenwood Printing. pp. 47–48. ISBN0313258627. OCLC 23253205.

- ^ a b William Henry Smith Memorial Library (1988). "Biographical Sketch, Schuyler Colfax" (PDF). Schuyler Colfax Papers, 1843–1884. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Historical Lodge. p. 2. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Brisbin, p. 361.

- ^ a b c d eastward Brisbin, p. 364.

- ^ Brisbin, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Brisbin, p. 365.

- ^ History of St. Joseph County, Indiana. Chicago, IL: Chas. C. Chapman & Co. 1880. p. 550 – via Google Books.

- ^ U.S. Congress (1913). A Biographical Congressional Directory. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Press Office. p. 560 – via Google Books.

- ^ Function of the Firm Historian. "Historical Highlights : Representative Schuyler Colfax of Indiana, January xiii, 1885". History, Art & Archives. Washington, DC: U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Precipitous, Walter Rice (September 1920). "Henry Due south. Lane and the Germination of the Republican Party in Indiana". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. Bloomington, IN: Mississippi Valley Historical Association – via Google Books.

- ^ Sharp, p. 107.

- ^ Brand, Carl Fremont (1916). The History of the Know Nothing Party in Indiana. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Academy. p. 74 – via Google Books.

- ^ Make, p. 74.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (2019). When the Irish gaelic Invaded Canada. New York, NY: Ballast Books. p. 161. ISBN978-0-3855-4261-six – via Google Books.

- ^ "THE KANSAS Lawmaking; Character of Primary Justice Lecompte" (PDF). The New York Times. July 12, 1856. Retrieved April v, 2019 – via The Times's print archive.

- ^ Hay and Nicolay (1890). Life of Lincoln, Vol. 3. p. 353,354.

- ^ a b c Abbot 1864, p. 282,283.

- ^ History.com Editors (Nov 6, 2009). "Battle of Wilson's Creek". History.com. New York, NY: A&E Television Networks, LLC.

- ^ a b History.com Editors. "This 24-hour interval in History: November vii, 1861; Battle of Belmont, Missouri". History.com. New York, NY: A&Eastward Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "The Failure to Reinforce Lyon". The New York Times. New York, NY. October 2, 1861. p. 1 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ "A Visit to Gen. Fremont". The New York Times. New York, NY. September 27, 1861. p. iii – via TimesMachine.

- ^ a b c "Gen. Fremont'south Form: The Other Side of the Example; Gen. F. Vindicated". The New York Times. New York, NY. October 3, 1861. p. 1 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ Weber, Lawrence (January 21, 2019). "The Frémont Emancipation Proclamation". Warfare History Network.com/. McLean, VA: Sovereign Media. Retrieved August one, 2021.

- ^ a b Phillips, Christopher. "Price, Sterling: Biographical Data". Civil War on the Western Border. Jefferson City, MO: Missouri State Library. Retrieved Baronial 1, 2021.

- ^ "Usa House Speaker (1863)". ourcampaigns.com . Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ "US House Speaker (1865)". ourcampaigns.com . Retrieved April five, 2019.

- ^ "U.s. Business firm Speaker (1867)". ourcampaigns.com . Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Rives, F. & J. (January 31, 1865). "Proceedings, January 31, 1865". Congressional Globe. Washington, DC. p. 531. >

- ^ a b c "Hon. Schuyler Colfax on the Political State of affairs" (PDF). The New York Times. September 20, 1867. Retrieved April 5, 2019 – via The Times's print archive.

- ^ a b Bain, David Haward (2004). The Former Atomic number 26 Road: An Ballsy of Rails, Roads, and the Urge to Go West. New York City: Penguin Books. pp. 65–half-dozen. ISBN0-14-303526-6.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h i j Joseph Eastward. Delgatto, Indiana Periodical Hall of Fame, Schuyler Colfax 1966

- ^ "The shortest period of service for a Speaker on record: March 03, 1869". Historical Highlights. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Ifill, Gwen (July 10, 1992). "The 1992 Campaign: Democrats; Clinton Selects Senator Gore of Tennessee as Running Mate". The New York Times . Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Hon. Schuyler Colfax on Italian Unity" (PDF). The New York Times. January ten, 1871. Retrieved Apr 7, 2019 – via The Times'south print archive.

- ^ Chernow 2017.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 1930, p. 298.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (2008). The Unfinished Nation: A Curtailed History of the American People (fifth ed.). New York City: McGraw-Hill. p. 409. ISBN978-0-07-330702-2.

- ^ "The 22nd Presidential Inauguration: Ulysses South. Grant March 04, 1873". inaugural.senate.gov. The Joint Congressional Committee on Countdown Ceremonies. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 753.

- ^ a b "Washington Gossip: Social Topics at the National Capital; A Visit From Schuyler Colfax" (PDF). The New York Times. February fourteen, 1875. Retrieved Apr 7, 2019 – via The Times's print archive.

- ^ "Schuyler Colfax Refuses" (PDF). The New York Times. April vii, 1882. Retrieved Apr 7, 2019 – via The Times's print archive.

- ^ Sloma, Tricia (November 9, 2011). "Pete Buttigieg becomes second youngest mayor in S Bend". South Bend, Indiana: WNDU – Channel 16. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ Humphrey, Jimmy C., ed. (January 1, 2015). "How Time has Changed... The Degree of Rebekah" (PDF). I.O.O.F. News. Winston-Salem, NC. p. xiii.

- ^ "Our Rebekah History". Official website. Rebekah Assembly of Idaho. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "The International Association of Rebekah Assemblies". Rebekahs in the San Francisco/San Jose Bay Area – website. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved April eleven, 2010.

- ^ William Raimond Baird (1906). Hand-volume of Beta Theta Pi. New York, NY: Published by the author. p. 297.

- ^ Hollister, 1886.

- ^ "Schuyler Colfax Expressionless", The New York Times, Jan 14, 1885, p. 1.

- ^ Kestenbaum, Lawrence. "The Political Graveyard: St. Joseph County, Ind". politicalgraveyard.com.

- ^ "Washington Park Historical Marker – Mankato, MN". Waymarking.com. Seattle, WA: Groundspeak, Inc. August 7, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Historic House Museums, Structures and Sites". Wayne Township Parks and Recreation Department. Town of Wayne, NJ. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ Titze, Anne-Katrin (January 9, 2013). "Speaking out about Lincoln: Bill Raymond talks about his office as Speaker of the House in Steven Spielberg's picture". Eye for Pic. Edinburgh, Scotland.

- ^ "Biography: Nib Raymond". Rotten Tomatoes. New York, NY. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

Books cited [edit]

- Abbot, John S.C. (1864). The History of the Civil War in America. New York City: Henry Nib.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN978-one-5942-0487-vi.

- MacDonald, William (1930). Allen Johnson and Dumas Malone (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography Colfax, Schuyler. New York Metropolis: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Rossiter Johnson, ed. (1906). Biographical Dictionary of America Colfax, Schuyler. Boston, American Biographical Guild.

Additional reading [edit]

- Hollister, Ovando James (1886). Life of Schuyler Colfax. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

External links [edit]

- Schuyler Colfax's signature on the 1864 joint resolution proposing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery

- Fremont's hundred days in Missouri : speech of Schuyler Colfax, of Indiana, in reply to Mr. Blair, of Missouri, delivered in the House of Representatives, March 7, 1862 at archive.org

- The life and public services of Schuyler Colfax: together with his most of import speeches at archive.org

- Schuyler Colfax letters, MSS SC 137 at 50. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Immature University

- U.s.a. Congress. "Schuyler Colfax (id: C000626)". Biographical Directory of the United states of america Congress.

- Schuyler Colfax Collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schuyler_Colfax

0 Response to "The Barnhart Family of South Bend, Indiana, Family Tree"

Post a Comment